The Power Behind Organisational Integrity

The recent Charity Governance Code‘s revised Integrity Principle represents an important step change for boards. Trustees must not only address power dynamics in the boardroom, but also in the charity’s purpose, practices and its people’s behaviour. [1]

To support charities, a group of us aim to develop an open-source Power & Organisational Integrity community of good practice and sharing. This blog shares the emerging thinking.

What do we mean by ‘organisational integrity’?

The word integrity has two meanings 1) honest/principled, and 2) whole/unbroken.

This double meaning captures the whole system approach that is needed. Ethics can often be viewed as within a department or a single part of how an organisation works. Integrity applies to all aspects of the organisation.

Organisational integrity is not limited to mitigating and addressing individual behaviour. It is about understanding and addressing overt, hidden and invisible biases as well as power dynamics that perpetuate inequality and harm. It also requires articulating and implementing responsible, accountable, and positive use of power by the organisation and its representatives.

Integrity & Oversight: What do boards need to know?

Three key steps to enable more holistic, coherent and effective board oversight of the multiple aspects of organisational integrity:

- View integrity issues as interconnected and requiring a ‘whole systems’ approach. (thoughts and a framework in this blog)

- Know which oversight questions can enable the organisation to move from a patchwork to a holistic and coherent approach (suggestions in this & the next blog)

- Understand and feel comfortable using power analysis through shared language and frameworks. (proposed frameworks in the next blog)

These complex dynamics can be better understood by drawing on the significant work on power by charities in their campaigns and programmes. However, the application of power analysis to charities is relatively new and, as highlighted in my previous blog post, is often myopic, occurring in clusters or silos. This incoherent and fragmented application by the board and executives undermines the organisation’s aims from the start. It can result in potential harm and risk going unnoticed, and ineffectiveness caused by different issues competing for precious resources and prioritisation. It can harm those it seeks to support.

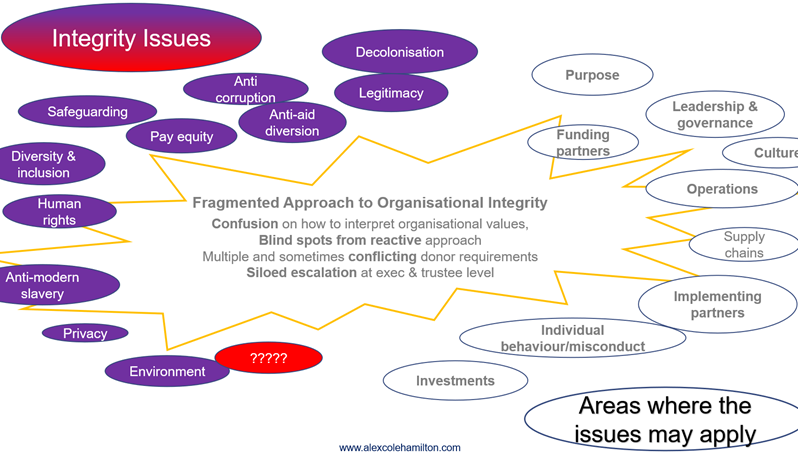

What are integrity issues?

Integrity issues stem from the unequal, irresponsible use and/or abuse of power at individual, organisational and wider levels. For example, slavery and sexual abuse are a result of broad systemic power imbalances which are exploited by individuals, gaining power from the very same structures that have made others vulnerable to that abuse. To mitigate harm, charities need to not only put in place controls to reduce the possibility of abuse, but also understand the interconnectedness of safeguarding and anti-slavery with deeper power imbalances around race, gender and other inequalities. These same power imbalances manifest in the charity sector as a lack of leadership diversity, pay gaps, and other forms of discrimination and unequal power.

Power analysis does not assume that all power is negative and problematic. By openly discussing power dynamics, charities can address the negative and encourage positive, accountable and transformative use of power.

Which aspects of the organisation need to be addressed?

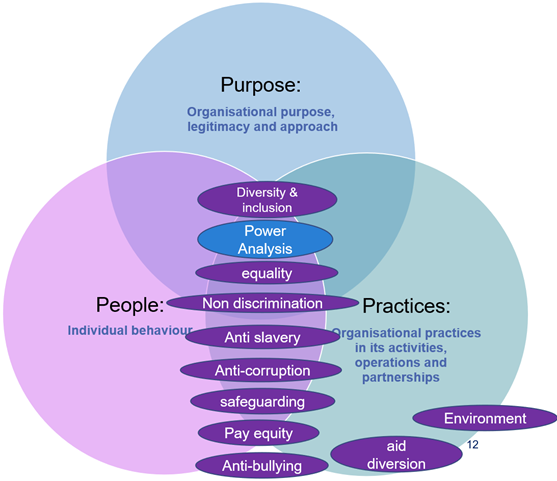

Charities’ aims and activities naturally fit into three areas: Purpose, Practices and People. Power analysis of these three areas can show how integrity issues intersect across the organisation.

Purpose: Power analysis at this level considers the wider context within which the charity works. It questions the charity’s aims, legitimacy, theory of change and approach. Responses need to involve and be accountable to those with less power.

- Core integrity issues include: diversity and inclusion, structural inequality, leadership style, and culture.

- Oversight questions for the board to ask: How might the charity be perpetuating inequality and causing harm, despite its intention to do good? How should responsible and accountable use of organisational and individual power be articulated, encouraged and held to account?

Practices: Power analysis here considers the charity’s activities, partnerships and supply chains. It supports the charity to align and inform its policies and processes across a wide range of issues.

- Core integrity issues include: Pay equity, diversity & inclusion, human rights, leadership style, culture, social and environmental impact etc.

- Oversight questions for the board to ask: How can the charity ensure non-discrimination and inclusion in its activities, partnerships and supply chains and be held accountable for it? What leadership behaviours should be set from the top to ensure that there is no abuse of power arising from/inherent in the charity’s practices? How are integrity issues embedded within practices?

People: Power analysis in this context is of behaviour, conduct and culture that shapes how power manifests and is used. It helps organisations understand when power may be abused, and to implement controls or adjustments to mitigate it . It also enables the organisation to articulate and incentivise people’s responsible and accountable use of their power.

- Core integrity issues include safeguarding, anti-corruption, anti-bullying, culture etc

- Oversight questions for the board to ask: How is the charity learning from its work to address misconduct to challenge existing practices that may enable that abuse? How is the charity actively taking steps to clarify, recruit for and incentivise behaviour? How is it supporting skills and leadership styles that align with the organisation’s view of responsible and accountable use of power?

Anti-slavery, safeguarding and safe programming: an example of a 3P approach

For many organisations, modern slavery strategies sit in procurement teams as this is where they perceive the greatest risk. Safeguarding, on the other hand, has evolved from the operational side of the organisation to address staff behaviour. Safe Programming, which addresses exploitation of beneficiaries by non-staff members, will often sit in yet another part of the charity. Focus on who does the exploiting rather than who is exploited results in a fragmented approach that is reported through siloed channels to the executive and trustee level.

Alternatively, if charities, took a holistic view of systemic power and exploitation they would more likely identify modern slavery risks with daily agency workers for emergency response work, office cleaners, or domestic staff. A power analysis approach would also help organisations to respond to modern slavery incidents with the same sensitive survivor-centred approach employed by safeguarding and safe programming teams.

Applying the 3Ps to enable a coherent approach on these and related integrity issues

Purpose – An articulation of organisational integrity and responsible use of organisational and individual power will enable a steer to understand, identify and mitigate risk of exploitation.

Practices – Charities look at how safeguarding, safe-programming and anti-slavery intersect with issues such as race and gender, and how those issues manifest in the charity as forms of discrimination, shape its culture and for example recruitment practices etc. Practices are revised in the context of a systems thinking/ whole system approach to mitigate harm and enable positive, accountable use of power by the organisation and its representatives.

People – Once viewed in terms of power dynamics, it becomes clear that to mitigate potential harm, the three issues need to be addressed in a more coherent a

This is a simple framework but it requires a fundamental shift that will require ongoing commitment, self- reflection, and support from donors. We hope that donors will align with the Charity Governance Code’s approach by recognising integrity and providing the resourcing and funding required.

The potential for harm is high with the existing patchwork approach. Undertaking such a significant shift may seem daunting, but it will be less stressful than the current fragmented approach – and more effective. Holistic organisational integrity will enable charities to move from reactive to proactive, responsive to transformational and a gain in supporter confidence, efficiency and impact.

To support organisations in this journey, we aim to establish a Power & Organisational Integrity community of good practice. We invite people to join as we develop an ‘open-source’ approach, building on existing work to support action learning and iterative development. We want to create a simple approach that accommodates both complexity and nuance. If you are interested to learn more, please get in touch [email protected]

_____________________________________________________________

[i] Charity Governance Code – Integrity Principle Outcome 3.5

‘No one person or group has undue power or influence in the charity. The board recognises how individual or organisational power can affect dealings with others’

Abridged Integrity Principle Recommendations 3.2 and 3.4

- Regularly check for inappropriate power imbalances in the board or charity.

- Where necessary, address potential abuse of power to uphold the charity’s purpose, values and public benefit.

- Larger organisations to have policies and procedures to ensure the charity has regard to the proper use of power and acts in line with its own aims and values